A critical care nurse, Zhan Liang knew her intensive care unit (ICU) patient had a rough, uncertain road to recovery ahead of him. As he was being discharged home, bedridden and on a mechanical ventilator, Liang was saddened by how severely weak and disabled many patients are after enduring a critical care experience.

“A lot of patients who survive the ICU can take years to recover,” says Liang, an assistant professor at SONHS.“I thought, ‘There must be an alternative way to help these patients get better.’”

Liang understood the challenges that nurses face in helping ICU survivors regain strength and mobility, as well as their ability to breathe on their own. One is the significant muscle atrophy, or wasting, that many ICU patients suffer after being confined to bed for days or weeks. Liang points to a 2013 study in JAMA (“Acute skeletal muscle wasting in critical illness”) that found 30 percent of muscle loss occurs in the first 10 days of an ICU stay. Various factors can speed up muscle atrophy, including being on a ventilator and the use of sedation drugs.

As nurses know, early mobility is key to preventing and treating muscle atrophy. However, mobilizing ICU survivors, especially those on ventilators, is a complex endeavor, Liang says. “It requires a resource-intensive clinician team, including nurses, physicians, physical therapists, and respiratory therapists. Most of the time, these health care providers are very busy, so patients do not get enough attention and their muscle loss worsens.”

This staffing issue becomes more problematic when ICU patients are transferred to non-critical care units.

The nurse-to-patient ratio can be one-to-eight or one-to-nine on these units,” says Liang. “Nurses are already very busy giving meds and taking care of other things, so patients may lie in bed without doing anything.”

Because of these challenges, Liang recognized that any new solution for reversing muscle wasting has to be easy to implement but stimulating enough to motivate very weak and often depressed or anxious patients to move and strengthen their muscles. It also has to be low-cost given current pressures on hospitals to rein in health care expenses.

After considering all these requirements, Liang thought of an inexpensive intervention that inspires countless people to exercise: music. In February, she and her team launched a pilot study at University of Miami Hospital to determine whether ICU survivors can begin to reverse muscle loss by listening to specially designed music playlists while performing simple exercises.

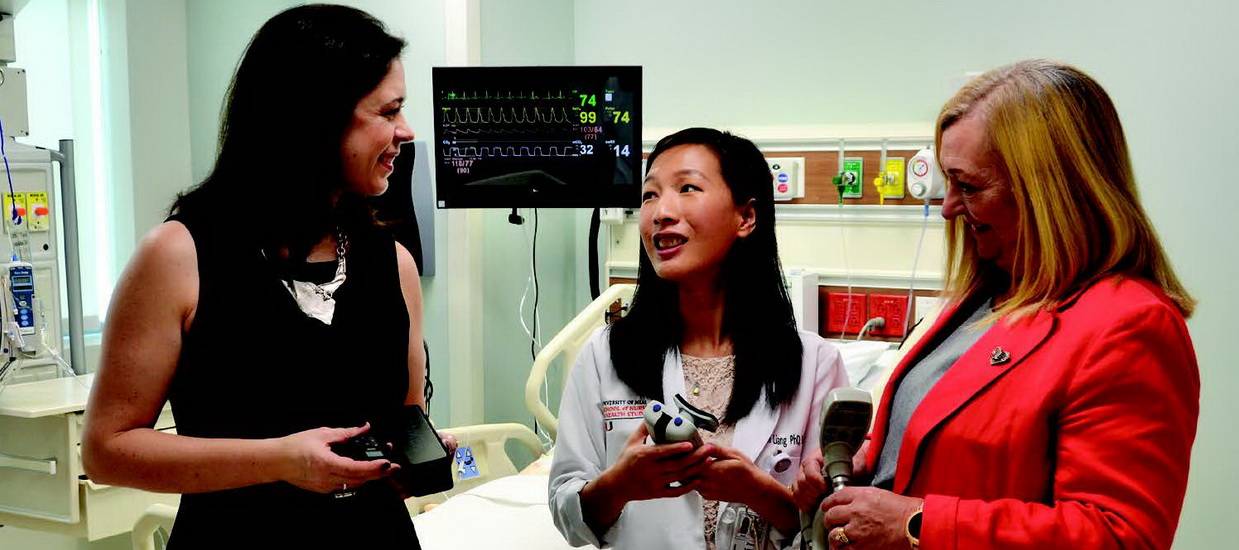

One of Liang’s co-investigators is Tanira Ferreira, a pulmonologist and an intensivist who is the chief medical officer for University of Miami Hospital. Also committed to the effort is Cindy L. Munro, dean and professor of the School of Nursing and Health Studies. “I have worked closely with Dr. Liang for over three years on NIH-funded projects with critically ill patients and am very proud to continue collaborating with her as a senior mentor on this pilot project,” says Munro, who has led intervention research aimed at improving safety and outcomes for long-term ICU patients for over two decades. “’Music-Enhanced Physical Exercise for ICU Survivors’ offers a novel approach to better understanding a significant but understudied issue for this vulnerable population.”

Healing with Music

Liang has already seen that music can benefit very sick ICU patients based on the research she conducted for her Ph.D. dissertation. While at the University of Pittsburgh, she worked with music therapists who created playlists designed to help ventilated patients manage their anxiety and learn to breathe on their own again.

When 23 subjects listened to these playlists during daily ventilator weaning trials, their heart rates and respiratory rates significantly decreased, compared to days they did not listen to music. The patients’ reported levels of anxiety and shortness of breath also improved on music days. Most important, the patients were able to stay off the ventilator for longer periods when listening to music.

Music engages every major region of the brain… [and] is a powerful tool for neuroplasticity and rehabilitation .explains co-investigator Sharon M. Graham, one of the music therapists collaborating with Liang. “When a patient is faced with a seemingly insurmountable goal of walking again after significant injury, hearing one’s favorite song can revive strong memories and feelings of love and happiness, releasing neurotransmitters like oxytocin into the body, which can elevate mood and decrease perception of pain.”

In addition to psychological benefits, music can help people learn and remember exercise routines. “Music can address motor goals specifically by providing a steady beat and temporal structure that actually primes the body for movement,” says Graham who is also founder and director, Tampa Bay Institute for Music Therapy.

The playlists being used in Liang’s study on music and exercise do not include popular workout songs. The ICU survivors are not exercising to Rolling Stones, Kanye West, or Taylor Swift. Rather, the playlists feature instrumental music with regular, metronomic beats specially designed to guide ICU survivors through a 15-20-minuteexercise routine.

With Liang’s guidance, Graham and music therapists from the Frost School of Music (Kimberly Sena Moore, assistant professor, and Hilary Yip, master’s student) wrote the musical pieces, which use rhythmic cues to remind patients when to, for example, lift their arm or put their arm down. The playlist was individualized for each patient in the study, taking into account the patient’s choice of instrumental music (i.e., piano, guitar, or wind instrument) and the pace with which the patient can perform the exercises.

Empowering Patients and Families

No prior research specifically looks at whether music-enhanced physical therapy can help ICU survivors regain muscle loss, Liang says. However, related research found that exercising to music improved physical function in patients with Parkinson’s disease, stroke, and other neurological diseases.

A recent nursing research award from the American Thoracic Society (ATS) Foundation funded Liang’s study on ICU survivors. “This highly competitive award from the ATS is a testament to the wonderful and impactful work Dr. Liang and her team are doing,” says Charles A. Downs, associate professor at the SONHS.

The ATS award made it possible for Liang and her team to purchase needed technology and resources for the research, including music software to create playlists, MP3 players for patients to listen to the music, and translation capabilities to help the research team communicate with Spanish-speaking patients.

Liang stresses that the initial study at the hospital is a small-scale pilot to determine the feasibility of the intervention as well as the potential of music-guided exercise to positively impact patient outcomes. The goal was to enroll 20 adult ICU survivors who have transferred from the ICU to anon-critical care unit at the hospital. All the patients were weak at the time of enrollment, having survived ICU stays of five days or more. However, they vary in age, disease history, and use of mechanical ventilation.

All 20 subjects receive the same exercise routine, which can be performed in bed or sitting in a chair. Five exercises target the shoulders, elbows, wrists, knees, and feet. The patients are encouraged to perform the exercise routine on their own at least twice daily for five days. Only 10 of the patients receive MP3 players loaded with individualized playlists and are taught to coordinate their exercises to the music.